Japan has some very unique New Year’s traditions, and one of the most famous is the food. Osechi, or traditional Japanese New Year’s cuisine, is as complex in its meaning as in its preparation. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at Japan’s beautifully festive New Year’s foods and the traditional meanings behind them.

Osechi was originally a religious practice; priests would offer special dishes to the gods on special days of the Chinese lunar year. It’s believed that osechi first came into being in the Heian Period, or around the mid-700s. By the Edo Period, or around the 17th century, osechi had become a household tradition. The dishes have grown more complex and decorative over time, but each has a root in Japan’s traditions and beliefs.

What’s in the Box? Osechi Dishes and Meanings

In modern Japan, osechi is eaten on January 1st, usually by the entire family and some extended family members. It is a common practice to leave the three- or four-tiered bento box in the center of a shared table. Everyone will take turns with the serving chopsticks and select their favorite foods from the bento box. A warning to those not used to Japan’s staple flavors: many osechi foods are traditional and may be a new flavor for you. Here are some examples of what to look for in a standard Japanese osechi layout.

エビ (ebi) – Long Shrimp, Long Life

One of the main osechi courses is bound to be a type of prawn. The long body, antennae, and legs of a shrimp make its symbolism clear: ebi represents longevity. A modern osechi course may have shrimp, lobster (which is also called ebi in Japanese), or both!

カズノコ (kazunoko) – Numbers of Children

Osechi will either boast カズノコ, herring roe, or いくら (ikura), salmon roe. The many numbers of fish eggs represent fertility. Kazunoko in particular accompanies this with a play on words, as the phrase 数の子 (kazu no ko) means literally “many children” in Japanese. The sound is the same, but the words are technically different. Everyone loves a good pun with their food.

だて巻き (datemaki) – Scrolls of Knowledge

Datemaki is a favorite staple of Japanese New Year’s osechi. If you enjoy the Japanese-style sweet omelet, you’ll probably like datemaki as well. This slightly sweet, slightly savory omelet owes its uniquely cake-like texture to the addition of はんぺん (hanpen), a type of fish cake. The datemaki is also more decoratively shaped than a classic sweet omelet, as it is usually rolled with a special bamboo mat called 鬼すだれ (onisudare). This gives the finished datemaki a grooved skin and keeps it firm yet deliciously soft. Datemaki represents knowledge and culture, as it resembles the scrolls that Japanese scholars read from in the old days.

昆布巻き (kobumaki) – Rolls of Kelp for Happiness

Kobumaki is one of those osechi dishes that might take some getting used to. Western visitors to Japan might not be comfortable with eating thick rolls of kelp, but you’re unlikely to find an osechi layout without kobumaki. These boiled kelp strips are often wrapped around a colorful fish like tuna or salmon and flavored with dashi or soy sauce stock. Kobumaki represents joy. This is a play on words, as the Japanese word for joy is 喜ぶ, or yorokobu.

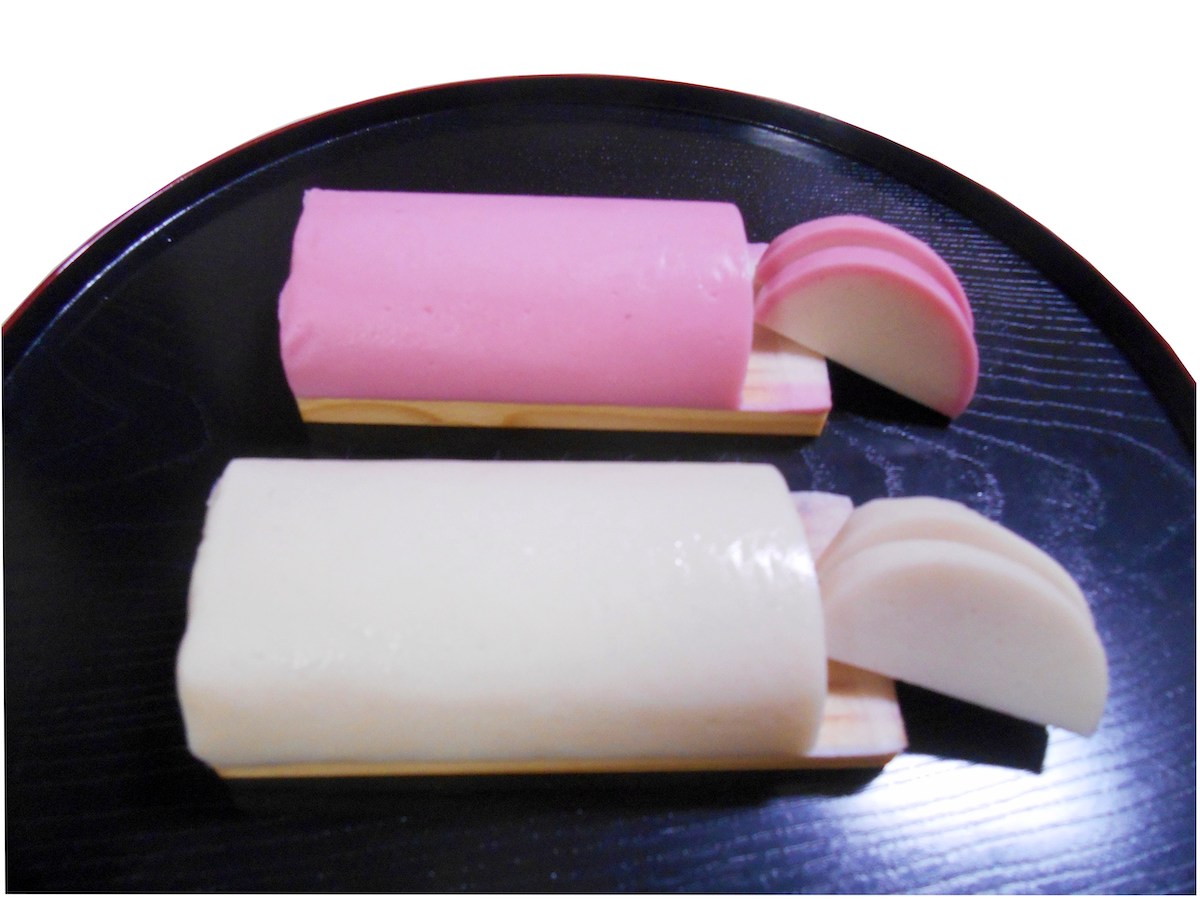

紅白かまぼこ (kouhaku kamaboko) – Sunrise, Yin and Yang

The colorful kamaboko fishcakes are often included in osechi. Due to their red and white (or both, as many are pink) tones, New Year’s kamoboko are called 紅白 (kouhaku) kamaboko. The theme of kouhaku features prominently in Japanese New Year’s traditions. Red represents evil while white represents purity. Team games and TV programs feature red teams versus white teams as festive New Year’s contests kick off around Japan. Kouhaku kamaboko adds this spirit of good vs. evil to your osechi bento. In addition to representing balance, the half-moon shape of the kamaboko cakes gives them the appearance of a sunrise.

田作り (tadzukuri) – Bountiful Harvest

This osechi dish features baby sardines that have been dried and baked in a sweet and salty sauce. While this may not sound appetizing to some, tadzukuri is more delicious than it sounds. Once you get past the fact that baby fish are staring up at you with their tiny, dead eyes, you can enjoy this New Year’s traditional dish with gusto. The history of tadzukuri is what lends to its symbolism in osechi: farmers in historic Japan would use the baby sardines to fertilize their rice paddies. Every fish was said to fertilize bounty of 50,000 rice grains, which gives tadzukuri its nickname ごまめ (gomame), or “fifty thousand grains”. Tadzukuri represents bounty for the New Year.

れんこん (renkon) – A Clear, Bright Future

Renkon, or lotus root, is certain to make its way into your osechi spread. The lattice-like pattern of the root’s many holes make it a decorative and delicious addition. Renkon is often simmered in a soy sauce, mirin, and dashi soup, or possibly pan-fried and glazed with a sweet and salty sauce. In Japanese Buddhism, renkon are associated with the holiness of a Buddha’s ponds. In addition, the many holes pocking a slice of renkon are believed to symbolize a foreseeable future, particularly one that is hopeful for the person eating osechi.

黒豆 (kuromame) – Protection and Health

These large, sweet, black beans are a sort of dessert in the osechi layout. Kuromame are stewed, sweet beans. Their black color is considered a repellent to evil spirits, and they also represent health and vitality.

栗きんとん (kurikinton) – Wealth and Fortune

Another osechi dessert, kurikinton is a sort of chestnut dumpling or mash. Its sweet, nutty flavor and beautiful yellow hue make it a big favorite amongst the osechi dishes. Kurikinton represents wealth and good fortune due to its similarity to gold.

Other Traditional New Year’s Dishes

Aside from the much-anticipated osechi, there are a few other traditional Japanese dishes that you can expect to eat during the New Year season. Some of these may be easier to make on your own than the complex dishes mentioned above. You might even be invited to make them with the whole family!

もち (mochi) – Rice Cakes

Mochi, or Japanese rice cakes, aren’t just New Year’s food—they’re also part of Japanese New Year’s decorations! As December approaches, you might notice small towers of the round, white cakes at the doors of homes and businesses. They are often topped with みかん (mikan), or clementine oranges. As December finally dawns into January 1st, that mochi is often taken inside and eaten. Since the sticky rice cake will certainly be hardened, families put this mochi into a warm soup called zouni. Just be careful when you’re eating the sticky mochi; it’s very easy to choke on if you don’t chew thoroughly!

年越しそば (toshikoshi soba) – Long Noodles for a Prosperous Year

A traditional New Year’s dish that has fallen out of favor with Japan’s younger generations, toshikoshi soba is a simple soup with Japanese buckwheat noodles, or soba. The long, thin noodles are supposed to represent prosperity and longevity for the New Year. Older Japanese people especially enjoy soba on New Year’s Eve. They will often go to an onsen (hot spring) and enjoy soba after a relaxing soak. While not the most flavorful food on this list, soba is a healthy, clean dish. You can add toppings like grated ginger or fresh chives, and depending on your choice of soup it can be quite delicious. Soba can also be served cold with a hot soup for dipping. No matter how you eat it, toshikoshi soba is a famous Japanese tradition.

Osechi: To Make or to Buy

It’s probably clear at this point, but making your own osechi is a laborious, complicated matter. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try it, especially if you enjoy cooking! There are many English resources for osechi recipes, often created by people who are living outside of Japan. You should be able to find good ingredients whether you live in Japan or not.

If you do live in Japan and don’t want to make your own osechi, that’s fine! Many Japanese people order their osechi from restaurants and grocery stores. This can get a bit pricey, especially if you plan to eat alone; most osechi bento boxes cost between 1万~4万 (¥10,000~¥40,000, or $100~$400). Such bento are usually designed to feed from 2 to 7 people. Tokyo Cheapo and other awesome websites have compiled lists of affordable osechi. Also, as 2020 continues to be a unique year with the pandemic limiting New Year’s gatherings, many stores are offering osechi for smaller numbers.

If you plan on ordering your osechi, be sure to do so in advance. It’s a very big deal to Japanese people, and families will want to be prepared ahead of time. Pre-orders for osechi typically open up in late October or early November; it’s best not to wait until the last minute!

Will you be trying Japanese osechi this New Year? Do you have a favorite osechi dish, or perhaps a traditional New Year’s food in your own country that you love? Let us know in the comments! Thank you for reading this article on Japanese New Year’s foods! 明けましておめでとう (akamashite omedetou)! Happy New Year!

Author: Erin Himeno