The Tokonoma — a few centimeters into the realms of gods

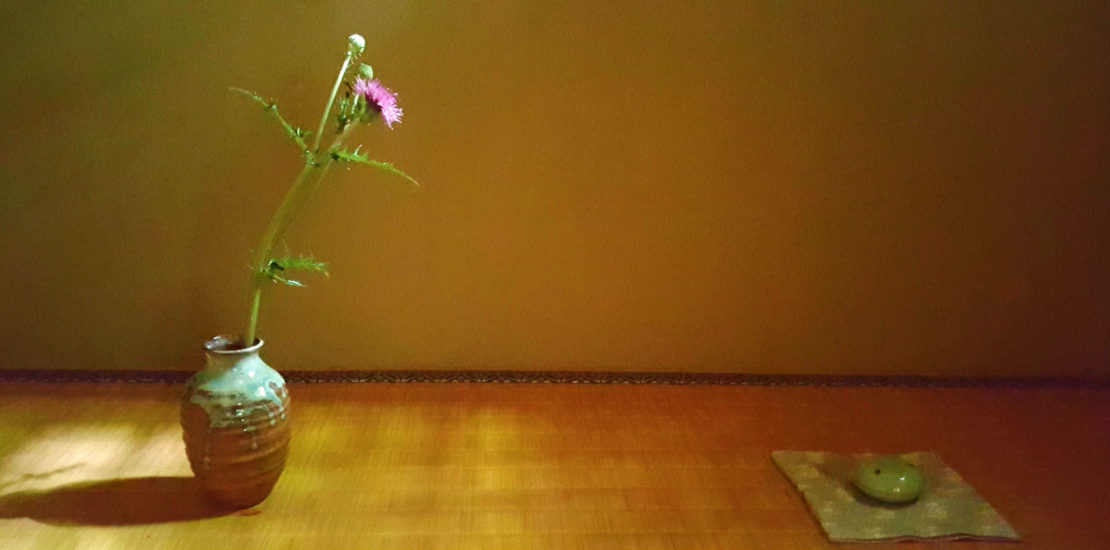

The tokonoma is an alcove that you can find very easily in any traditional Japanese house. I say it is easy because it is generally very visible in the living room. That being said, to some extent, it very often looks a bit dark, a bit apart from the rest of the room. Elevated in the form of wood board or a tatami, sometimes very narrow in width, often deep, you can notice that a big pillar of rough wood is nearing one of its corners. In the tokonoma, there is calligraphy hanged, or sometimes a flower arrangement or a Buddha.

If you research the tokonoma, you will quickly find explanations on the do’s and don’t’s regarding that space. You learn that it is a place of display, not a place to walk in. The most basic info would be: it is a ‘sacred’ place, please do not do anything to it and politely respect it if you do not want to concern your host.’ Then a bunch of descriptions of its history will pop up here and there. You will almost learn nothing of why there is a need or, even, a benefit, in having a sacred space.

Creating a space for respect

In our modern world, it has now become a cliché to say that nothing is sacred or that we all have lost the sense of the sacred. Such consideration is, of course, a caricature of reality. Rather than saying that there is no sacredness anymore or that there is no such thing as a feeling of sacredness today, I would argue that we live in a feeling that we lack sacredness.

To my knowledge, every culture has known the concept of sacredness in one way or another. There is always something, some thought or someone that cannot be touched in a normal way. And maybe this is simply a good way to make a difference between the purely material and what some call the spiritual.

This frontier is essential because, otherwise, we might end up treating ourselves as purely material beings. Or rather— and this is the real issue: we might be treated by others as purely material beings. To prove my point through absurdity: it is acceptable to handle a plastic bottle without care, playing with it and eventually crushing it, but what if others did the same to us?

Please consider this article as purely agnostic, devoid of any particular belief in any text or social practice related to religion. I am not the advocate of any religion here and I would not try to defend the need or the uselessness of religions in our modern societies. But it seems to be a matter of fact that our sense of the sacred is closely related to the development of our sense of respect. There are certainly other ways to develop that sense of respect, but I would like to question this: how does the tokonoma, through its aura of sacredness, can change our perception of space and of others, our very practice of respect?

It is said sometimes that the tokonoma comes from the Japanese tea ceremony and was later popularized in Japanese homes around the 17th century. It is true that its popularization came through the tea ceremony, but its origins drawback to the Buddhist altar and…to politics.

In some periods, in Japan, the hierarchy of the lords was determined in space by a single step of barely 10cm. The Highest lord’s tatami just had to be above the others. If you go to the reception room of Nijô castle in Kyoto today, you would still see this. There is no tokonoma with tatami in the room (just a shelf), but there are two elevated tatamis in the back, next to the golden wall, then five or six rows of tatamis below; then another step and about ten rows of tatamis again. Depending on your rank in the court, you would be higher or lower on the tatamis. And the highest tatami, of course, is only for the highest lord.

In ancient practices of tea, there was no peculiar display of items in the alcove: this was where the lord sat. To show greater respect, to indicate the sacred status of the person, you would sit that person higher. This is nothing peculiar to the Japanese, of course, but it has its importance to understand the meaning of the tokonoma. Because it is not a place forbidden for humans, it is only a place closer to the gods in the sense that, in that space, the respect given to things is like the respect given to gods. A flower can be a god, calligraphy can be the words of gods. But it is not because this calligraphy is godlike that it is in the tokonoma. Rather: it is because it is in the tokonoma that it is perceived as godlike. In other words, our sense of sacredness, our sense of absolute respect, is something to be trained, and the tokonoma is actually a place to teach us that. Whether it is calligraphy, flowers or someone, in the tokonoma, that being must be treated with care.

Tokonoma trains your sense of respect

The function of this sacred space, when it came into Japanese houses, has changed. Since the displays started to be less related to daily peculiar occasions as in tea, and more to daily life, a sense of exceptionality could not be created. Nevertheless, just like some people take their shower every morning, some Japanese go and get a flower, choose calligraphy or painting and arrange the tokonoma. Maybe this is training. Training to learn self-respect and respect for others. Every day, I try to keep a space of respect in my house and it reminds me to respect every being. So a well-curated tokonoma in a Japanese house does not simply mean that there is a god in the room, it means that its owner has a sense of sacredness, a sense of respect and that sense can thus apply to the way this owner is treating you.

Whenever my house gets too messy, I go out and pick a flower. I come back home and think carefully about how I wish to display it. And when I have put the flower in my tokonoma, I realize how messy my room is and I start to clean: I learn to respect my self, to respect my space and to respect the guests that might come.

I remember seeing, in a friend’s house, that her tokonoma was just full of items, like a shelf to throw out keys and small change. There was not a single space protected from our mundane activities. Not a single meter square where the mind could breathe, freed from the material world and able to focus on the spiritual aspect of things. Just like a professional violinist is barely noticed when he plays in the subway of New York, the few tea bowls lying around could not be seen as beautiful. They had lost their aura. I do not think that anything is sacred in itself, but I think it is important to produce sacred spaces for ourselves.

Recently, as I entered a tea room in Kyoto, I was struck by the exuberant flower arrangement I saw. In this tiny little hut, hidden behind a temple in ruin, my host had meticulously cleaned the space and prepared a gust of life for my eyes. Flowers sprung in every direction from a long black vase under a single light. All the ragged life of the filthy temple I had seen, with its rotten tatamis and its piles of wood garbages, had made me quite sad. So much human work had gone to waste and even the moss was dying around the stones. Beholding the flowers in the vase, I was reassured: there is still a gardener here, someone is taking care of the living beings, life is cherished.

The tokonoma had placed these flowers higher than the ordinary world. Everything seemed to matter again. Sometimes, it only takes a few centimeters…

Thank you for reading this week’s blog!

If you are having trouble finding a place in Tokyo, please feel free to contact us and have a look at our properties at tokyoroomfinder.com. We will connect you with your desired house at no cost!