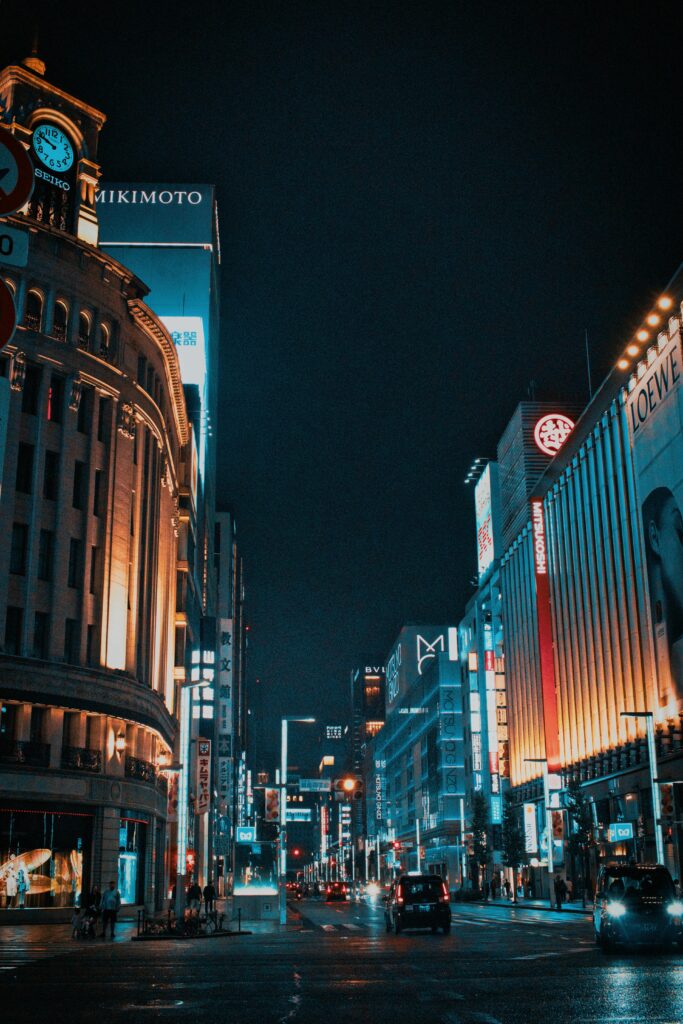

The name has become synonymous with luxury and opulence. And shopping in Ginza feels like your wallet had an argentoctomy. But watching is free, and more than worth it. Read on to find out more.

It is one of the most accessible parts of Tokyo, and also one of the most iconic. But it is all built on sand — or rather, mud. As late as 500 years ago, ships, even big ships, could sail to where Tokyo Station is today. But already before Edo became Tokyo, the shogun decreed that the mud flats should be turned into dry land, expanding the city in the eastern direction.

Expanding on the mud flats of Ginza

The expansion started with Ginza, which was a swampy shore of Tokyo Bay in the Edo era. Now you can hardly believe this ever was anything but firm land. But what was a conservative office and banking area in the 17th and 18th century (the name means ”silver seat” and was coined after the mint was established here in 1612) became a pile of rubble in 1872, after a fire devastated the area.

A Brick-Built Modern Ginza Showcase

Edo was a city of wooden buildings, with paper screens and straw tatami mats, and it was burned like a cinder several times. Tokyo had one of the first fire brigades in the world — but they could not save Ginza.

So when Ginza burned the last time, the Meiji government was not as keen as the shogunate had been on rebuilding it in the same old style. Now, modernization was the order of the day, and here was a perfect opportunity to show that Tokyo could be something other than a quaint Japanese traditional city.

The plans called for a modern city of brick buildings between Shimbashi station and the foreign enclaves around Tsukiji (the only thing remaining of that today is St. Luke’s hospital). Suitable clay for the bricks could only be found as far away as southern Tochigi, where industrial brick kilns sprang up, the one in the small town of Nogi remaining. The railroad network was yet to embrace Japan in its current iron grip, so the bricks were ferried on the ancient river network that used to be the main transport artery of the northern Kanto region.

Hated by foreigners

Foreigners hated Ginza, maybe because the modern brick buildings reminded them too much of home. The tourist guidebooks of the time, spluttering over rustic villages and quaint back alleys, found it coarse and vulgar. It was even compared to Broadway — although that was not a compliment.

But the Westernized city became a hit with locals, who, of course, had never seen anything like it. Strolling on the broad avenues between rows of yellow brick buildings made them feel they were visiting a foreign country, as yet an uncommon privilege for both Europeans and Americans, and an extra thrill for the Japanese, who, less than a generation ago, had lived under a harsh dictatorship that prohibited all but a tiny trickle of foreign cultural imports.

Fashion, Freedom, and the Rise of Ginza

Naturally, the strollers were not the only ones keen to use their newfound freedoms. Freedom of the press was one such, tasting extra sweet after four hundred years of oppression. Several magazine publishers made Ginza their home, contributing to the reputation of the area as a fashion haven, as did the display windows of the stores, a novelty to most Japanese.

Ginza was also the target of the first subway line in eastern Asia, the eponymously named Ginza line.

Not much remains of that original brick city, thanks to the WWII bombings and relentless redevelopment. Most buildings in Ginza are new, dating back less than 70 years — in many cases, even shorter, where they are showcases that have to be refreshed to impress an increasingly stingy clientele.

But the iconic Wako department store, and its famous clock tower (originally built by the founder of Seiko), are from 1894. Every Sunday, traffic on the busy thoroughfare outside is shut off, and the street is turned into a pedestrian strolling ground.

Today, the pace of redevelopment sees buildings across Ginza, especially the grand showrooms of the international brands, regularly torn down and reconstructed. The Armani building has changed more than once; the Sony Center was redeveloped until the company fell on hard times and sold it. There is continuous construction going on in Ginza, and even as the economy is suffering, the hoi polloi of Japan do not seem to find the ever-increasing prices of imported goods anything but an inconvenience.

Walking inside a magazine

Walking down the streets of Ginza feels like walking inside a high-end fashion magazine. Here, a Valentino store, there Dior; next to them Cartier and Gucci. Jewelry and watches do their best to outshine fancy clothes and iconic brands. And sprinkled among them are quietly expensive high-end eateries, focusing on the clientele who can afford it.

The occasional antenna shop — where other prefectures feel the mood of Tokyo with their local specialities — dots the streets, offering a reprieve from the relentless commercial sales push, and (in the Hokkaido antenna shop) better soft-serve ice cream than anywhere else.

But perhaps the most interesting part of Ginza is the kabuki theatre. Not the kabuki-za building, the only remaining permanent stage for the traditional Japanese theatre, which was rebuilt at the beginning of the 21st century to also house a huge office complex. No, the interesting part of kabuki is the theatre itself, famous for its exaggerated makeup, men playing women, hugely elaborate stage machinery, and fierce dances.

Kabuki and Culture in the Heart of Tokyo

Many of the plays performed today were written during the grand era of kabuki in the early 19th century, before modernisation was allowed, but while the peak of homegrown Japanese forms of expression sought to renew themselves. It is not that hard to get tickets, and there is often an English rendering of the story in rental headphones, which is well worth it.

During the Edo era, kabuki was one of the few allowed forms of entertainment. Competition between the theatres was fierce, and they sought various ways of attracting customers. One of the most effective ways was to put up advertising woodcut posters with pictures exaggerating the makeup and gestures of the actors. During the Edo era, they plastered the city. Today, those woodcuts are rare and appreciated as a unique Japanese form of expression — the ukiyo-e.

Stay tuned for more exciting content like this! Follow us on our social media platforms and check out our blog regularly to stay updated on the latest news, trends, and insider stories from Japan. Don’t miss out on future updates — sign up for our newsletter for exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox!