There seems to be a ramen restaurant on every street corner in Tokyo. There are only three with Michelin stars, and getting a reservation takes long advance planning. So how do you know which of the many restaurants is worth visiting? Read on to find out more.

All About Ramen

There are hundreds, if not thousands, of ramen restaurants in Tokyo. Ramen is the number one soul food for the Japanese (possibly competing with soba, udon, and karaage).

While there are a ramen restaurant on close to every street corner, there are only three with a Michelin star in Tokyo. The Michelin guide lists 19 ramen restaurants worth visiting. But if you are not a serious ramen fan, you are not likely to think about making a reservation well enough ahead.

So faced with several restaurants that look more or less the same, how do you know if the quality is worth the price? You can not trust guidebooks (they quickly get old) or review sites (which can be easily manipulated). You have to take a good look at what the restaurant shows you, and that does not mean the plastic samples outside the location.

Three Components of a Perfect Bowl of Ramen

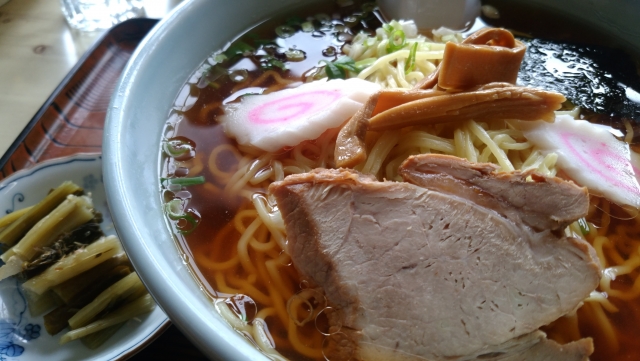

A serving of ramen has three components: the soup, the noodles, and the garnish (the Japanese word ”飾る (kazaru)” is usually translated as “garnish” but means more like “additions which bring taste”).

There are movies (the best – and funniest – is “タンポポ” (tanpopo)) about cooking ramen. There are TV programs following the chefs as they work all day and night to tease out every molecule of taste into the soup. The soup – which you do not drink – has an almost mythical status in Japanese ramen cuisine. Scratch “almost.”

And there is no lack of variation in the kind of soup you can be served, either. Just within the ramen area, because nearby is tsukemen (where you dip the noodles in the sauce) and the many varieties which are based on, or come from, Chinese cuisine. Like tantanmen, which is essentially ramen served with a spicy Chinese sauce.

But even disregarding the Chinese cuisine (and newer variants such as italian ramen in tomato soup; and tom yam kung ramen), there are tonkotsu ramen (with a soup made from pork bones that contain the nerves and fatty membranes embedding them, turning the soup white); and miso-based soup, that typically is made with spicy miso. But there is also clear pork broth, and chicken soup, and fish broth (made from tuna bones), and any of a mix of any of them, at any stage of the cooking process, the way to tease out taste the secret of the chef.

Typically, Japanese restaurants can be one of three kinds: Part of a major chain, where you will be served standardized fare and know exactly what you will get and nothing more. Then, there are regional chains, that originated in one single restaurant and have expanded to two or three stores. And finally the owner-chef restaurants, where the restaurant is the life, and the life work, of the owner.

While Japanese customers appreciate the consistency and (usually) reasonable prices of the chains, they also know that there will not be any variation. You will not find a franchisee of a major chain staying up all night to wait for the pork bones to soak slowly so they can add the tuna bones at the exact right moment.

The Ramen Noodles Come Second

The second part of a serving of ramen is the noodles (“men”, the second part in the name of the dish “拉麺”, usually written with katakana “ラーメン”, actually means noodles). Many restaurants – not only chain stores – get their noodles from a factory. There are two philosophies about this: some noodle makers make better noodles. Using noodles from one of those will give you better ramen. Or, the craft is all, and the restaurant that provides hand-made, home-made noodles is giving better service than the restaurant that uses factory-made noodles.

Heated discussions will emerge along the ramen restaurant counters if you bring this up, but the truth is that different from udon, the other dominant wheat-based noodle in today’s Japanese kitchen, ramen are better if they are not entirely fresh. Udon chains like Marugame Seimei make their noodles in the store. You are supposed to massage the dough (in smaller restaurants, by stepping on it) before you cut the udon, as this (just like kneading bread) helps the gluten form longer molecule chains which makes the noodles more chewy.

That, however, is not true for ramen. Ramen noodles are made with an alkaline water, not ordinary water and wheat flour, which is what udon is made with.

This means that more effort has to go into the preparation of ramen noodles, and that they actually gain from being stored for a few hours before being boiled, differently from udon and soba, which can be prepared in the store. It also means there are ramen noodle makers, often small local factories, serving the nearby city.

Just like considerable effort needs to go into the preparation of ramen soup, so does the preparation of the noodles. But choosing and sourcing the right flour, alkaline water, and other ingredients that go into ramen noodles is not simple; it is a lot to ask of the store manager (or owner-chef) that they should be experts in both purchasing flour and preparing noodles, although of course the real Michelin-star class top of the line ramen restaurants do.

Running out of noodles

You can often see the delivery trucks and delivery boxes from the ramen factories in the entrance to the stores. They are one reason why restaurants may close before their advertised closing time – they have simply run out of the ramen noodles they ordered for the day, and are forced to close since they have nothing left to sell. You can look for the delivery boxes in the entrance, and if it is a well-known brand, you know the noodles will be good. Or at least not bad.

The last part of the meal is the garnish, but it is arguably as important for the taste and experience as the soup.

Traditionally, ramen noodles are served with a couple of slices of roast pork (which goes by the Chinese name char-siew), a leaf of nori, and a boiled egg. There is also a small piece of fish cake (kamaboko) in the soup (it is the pink slice). The char-siew is often prepared in the store, with the same care that goes into the preparation of the noodle soup.

Many restaurants also serve bean sprouts in the soup; this gives a nice change of texture, but may not be according to strict ramen lore.

The most effective way to identify the best ramen restaurant on a street, however, is also the simplest: Look for a place where customers line up before opening, and get in line. They will be serving ramen worth waiting for.

Stay tuned for more exciting content like this! Follow us on our social media platforms and check out our blog regularly to stay updated on the latest news, trends, and insider stories from Japan. Don’t miss out on future updates—sign up for our newsletter for exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox!