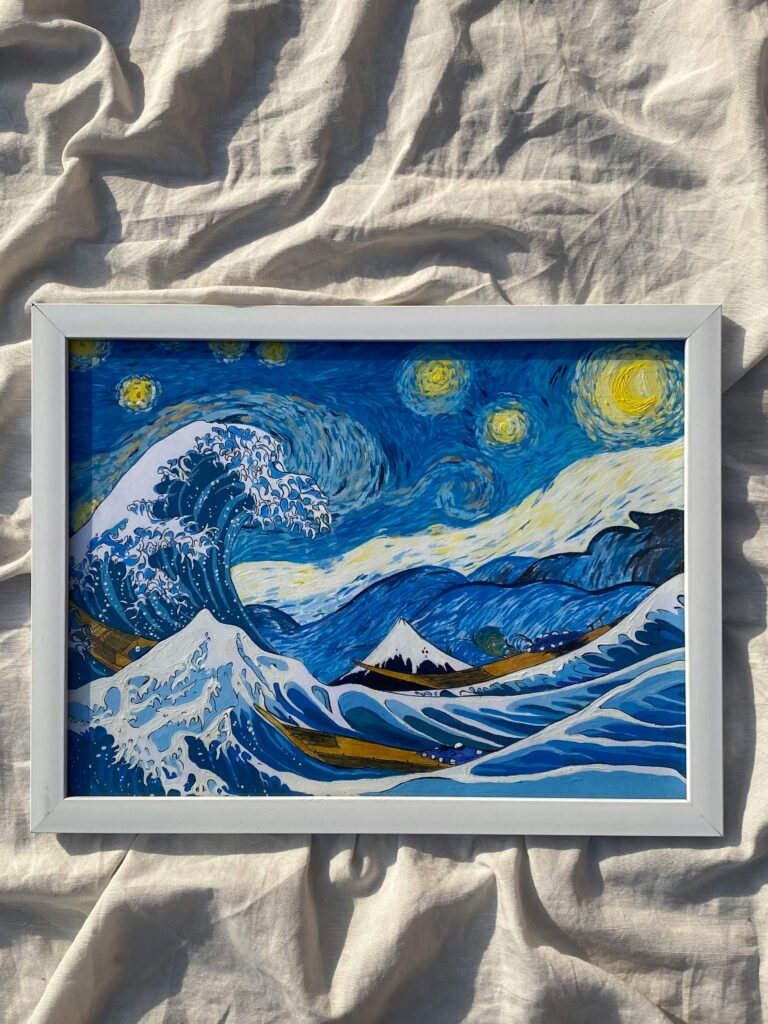

Japanese visual arts have an incredibly long history. But the Tokyo art museums are not restricted to traditional Japanese arts. You will find several classic works of art by artists such as van Gogh, but also specialized museums showing traditional arts, the workshops of individual artists, and everything from design to manga sketches. Read on to botanize.

Tokyo is home to almost 100 art museums (sometimes the definition can be a bit blurry), and this reflects the intense passion of the Japanese for the visual arts. But the museums are naturally open to tourists as well, and if you are have even the slightest art interest, you are in for a treat when visiting Tokyo.

Here is a collection of some of the must-visit museums, but do look at the map and try to find the preserved studios of artists that dot the special wards of the city. They dot the cityscape in areas such as Meguro, where land was cheap when the artists started integrating the traditional way of expression with new concepts from Western art.

Tokyo’s Art Museums: Quiet Rooms in a City That Never Stops Talking

What makes Tokyo’s museum landscape distinctive is not just quantity, but intent. Japanese sources consistently emphasize context: museums are designed not as isolated boxes, but as environments—linked to gardens, architecture, neighborhoods, and daily life. The art is important, but so is how you arrive at it.

Ueno: The Civic Heart of Tokyo’s Museum Culture

If Tokyo has a museum district in the Western sense, it would be Ueno Park. Established in the Meiji period on former temple lands, Ueno became a symbol of modernization through culture. Japanese historical references describe the park as one of Japan’s earliest public spaces dedicated to education and enlightenment.

The Tokyo National Museum, founded in 1872, anchors the area and is Japan’s oldest and largest museum. Its collections—spanning Jōmon pottery, Buddhist sculpture, samurai armor, and classical painting—are often described in Japanese museum literature as a narrative of Japanese civilization rather than a simple display of objects. The museum’s layout reinforces this: visitors move chronologically and stylistically, not just visually.

Nearby, the National Museum of Western Art tells a parallel story. Based on the Matsukata Collection and designed by Le Corbusier, the building itself is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Japanese architectural commentary frequently points out the irony—and success—of housing Western art in a modernist structure created by one of Europe’s most influential architects, right in the middle of Tokyo. Together, these institutions make Ueno less of a “tourist stop” and more of a civic classroom.

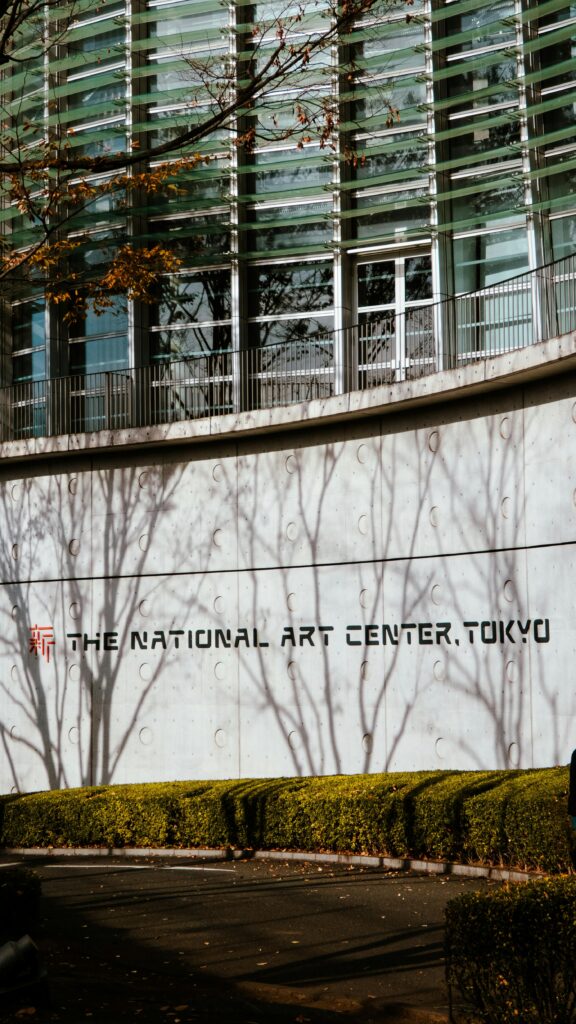

The National Art Center, Tokyo: A Museum Without a Collection

One of Tokyo’s most quietly radical museums sits in Roppongi: the National Art Center, Tokyo. It owns no permanent collection. Instead, it functions as a rotating exhibition hall, hosting major domestic and international shows.

Architect Kisho Kurokawa’s wave-like glass façade is often discussed in Japanese architectural writing as a symbol of openness and flow. Inside, the museum feels less like a temple and more like a public plaza. You can enter without a ticket, sit in the atrium café, and simply exist among people who came for different reasons.

This accessibility is intentional. The museum’s mission, according to official descriptions, is to lower the psychological barrier to art.

This makes the National Art Center emblematic of Tokyo’s approach: art as something woven into daily life, not elevated onto a pedestal.

Roppongi’s Cultural Triangle and Museums

Roppongi has rebranded itself over the past two decades, and museums were a major part of that strategy. Japanese redevelopment documents often refer to the area as a “cultural hub,” anchored by three major institutions: the Mori Art Museum, the Suntory Museum of Art, and the National Art Center.

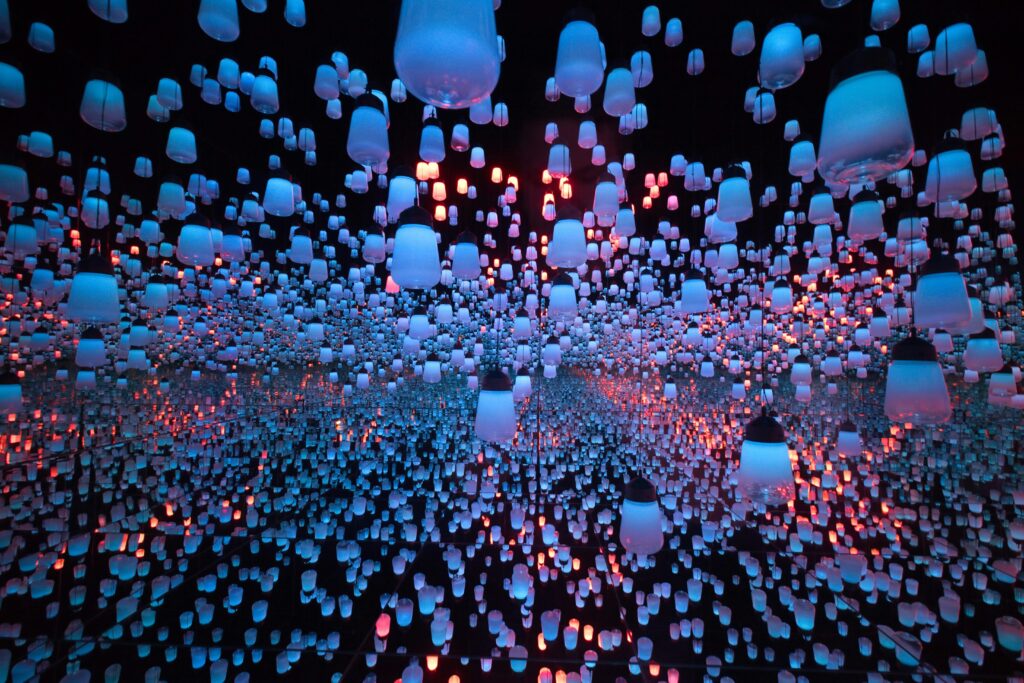

The Mori Art Museum, located atop the monumental highrise Roppongi Hills, specializes in contemporary art with a global outlook. Its exhibitions often address urbanism, technology, and social change—topics that resonate strongly in Tokyo.

Japanese commentary frequently notes the symbolic power of placing contemporary art above the city, literally. You look at works that critique modern life while the city spreads out beneath your feet.

By contrast, the Suntory Museum of Art defines itself with the phrase “Art in Life.” Its focus on traditional crafts—ceramics, lacquerware, textiles—positions art not as something separate from daily existence, but as an extension of it. This philosophy appears repeatedly in Japanese museum texts and reflects a broader cultural idea: beauty is functional.

Museums That Disappear into Green

Tokyo’s museums often hide themselves. The Nezu Museum in Minato-ku is a prime example. After its renovation by architect Kengo Kuma, Japanese architectural sources praised how the building recedes into bamboo groves and gardens. The approach path is long and deliberately quiet, creating a sense of separation from the city before you even see a single artwork.

Inside, the Nezu’s collection of pre-modern Japanese and East Asian art—especially Buddhist sculpture and calligraphy—is presented with restraint. Labels are minimal. Light is controlled. Silence is expected. The museum experience mirrors traditional Japanese spatial aesthetics, where absence and pause matter as much as presence.

The Adachi Museum of Art is often cited internationally for this approach, but Nezu shows that Tokyo itself has mastered the art of letting nature and architecture do half the curatorial work.

Contemporary Voices: Smaller but Sharper

Beyond the major institutions, Tokyo’s art scene thrives on smaller, highly focused museums. The Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, tucked into a quiet street in Shibuya, is often described in Japanese art writing as “experimental” and “intimate.”

Its exhibitions challenge viewers without overwhelming them, reflecting Tokyo’s preference for depth over spectacle.

Similarly, the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in Ebisu occupies a niche that feels almost modest in a city saturated with images. Japanese sources emphasize its role in legitimizing photography as fine art in Japan, balancing domestic photographers with international figures. It attracts visitors who come specifically to look, not to be seen.

Design, Art, Architecture, Museums and the Blurred Line

In Tokyo, the boundary between art museum and design museum is thin. The 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, also in Roppongi, was founded with the explicit goal of examining everyday design. Japanese descriptions highlight its mission to question how objects, systems, and environments shape daily life.

Designed by Tadao Ando and partially underground (in the grounds of the Tokyo Midtown complex), the building reinforces this idea physically: design is not always visible, but it supports everything above it.

Exhibitions range from fashion to industrial processes, reminding visitors that Tokyo’s aesthetic intelligence extends far beyond galleries.

Why Tokyo’s Museums Feel Different

What ties Tokyo’s art museums together is not style, scale, or even subject matter—it is attitude. Japanese references consistently frame museums as places of use, not monuments. They are visited alone, on lunch breaks, between errands. They are not reserved for special occasions. They are as everyday as your neighborhood Starbucks.

Stay tuned for more exciting content like this! Follow us on our social media platforms and check out our blog regularly to stay updated on the latest news, trends, and insider stories from Japan. Don’t miss out on future updates — sign up for our newsletter for exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox!