Being a journalist in Latin America is a very ungrateful job, in some countries it can even cost you your life. That was not my case though; I just had a very demanding job for a very low salary. Now some might say: “But Erica, isn’t that everybody?” I will answer to that by saying that most people have better opportunities in within their own line of work, journalists don’t: a journalist can be very well payed, but that journalist would be giving their whole time to that job exactly like that new guy that just got in a company. I wanted my time back.

I found out about the MEXT scholarship when I was 19 years old and it took me fourteen years to apply to it. I can’t say that I had a fanatism for Japan like many other foreigners do. I knew about Japanese culture, I’ve watched mangas and animes, like any other person who was a child and a teenager in the 90’s in Argentina (my country). I got my information about Japan from those audio-visual products. I knew J-rock, but I didn’t follow any of the bands. Till this day when people ask me “Why Japan?” I still don’t have the answer. However the connection with Japan had been there my whole life.

Anyway, when I finally found my reason to come to Japan, it was my education. Granted, the exit from my country was dramatic: I sold everything I owned (including my clothes), I left my job and jumped on the plane. If it sounds like I was running away from something, it might just be true. However, spoiler alert, it was the best decision I’ve ever made. Kyoto was the place that opened the doors of Japan for me. I arrived in Kyoto on a rainy night and spent too much on the taxi ride to my new home. It was 9:30 pm and my new life had just started. The ride was long, from Kyoto Station to Kitashirakawa, it took around thirty minutes. Later I would found out that, if you take a bus, it can take a little more than an hour. Kitashirakawa is where I learned that Japan is not as different from the rest of the world or like media might make it to be. Kitashirakawa is a family neighborhood, with little parks, with elementary schools and parents riding bikes carrying three kids on them. Exactly like my neighborhood back at my home country. Bikes in Kyoto are far more dangerous than cars. When you are so out of your element, when the language doesn’t share even an ounce of resemblance with your own, small things that might have seem irrelevant before got suddenly problematic. Such was the case of my first visit to the supermarket. The only thing that gave me some peace was the fact that the name of the place was in Spanish, my native language. Other than that, the rest was all in Japanese, as it should be. I managed to buy tea and other items with brands that were also in my country so I knew what the products were. The order was a loaf of bread, Knorr instant soups and something that I prayed was sugar, it was. For a week I fell asleep at 6 pm and lost two kilos just trying to make my body get used to the time, the fact that it was spring and that that wasn’t my bed but that I was ok anyway. I also wanted to find a phone somewhere, I did, but when a three to five minute call costed me around ten dollars, I knew that I had to buy a phone immediately.

Kyoto was the place where I learned Japanese for the first time in my life and where I made new friends. As a fully grown woman, I didn’t have that many opportunities or that much interest in making new friends; but Japan made me. The Japanese language course was at the renowned Kyoto University, where people from all over the world seem to converge. I made more new friends and I felt terrified about the language. Many times, while in the classroom, I used to look around and think to myself: “What are you doing here?” “Here”, surrounded by twenty year olds, feeling more like a high school student than a university one. However, before coming I promised myself that I was not going to pay excessive attention to the negative thoughts, to the dark corners. I had decided that I was going to enjoy and to learn about everything. Spoiler alert number 2: I learnt Japanese, how to make friends, how to be friend myself and so much more.

After that introduction, the real world started. The university in which I studied for my Master’s degree is a women-only university, Nara Women’s University, something unheard of in my country; in a town that I had never heard of, Nara. When you look up “Nara, Japan” in Google, you get a bunch of pictures of people in a park with deer. There are no crowded streets, no crazy advertising banners or people with questionable (or fabulous) fashion taste. I was not that happy about the result, but like I said before, I refused to see anything bad about this opportunity. I was doing the right thing.

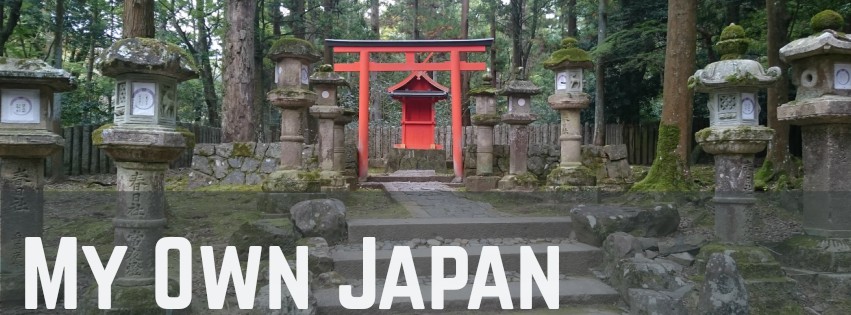

The first time I came to Nara was in a warm September day, perhaps too warm. I got lost and arrived in JR Nara Station instead of Kintetsu Nara Station which is closer to the university. My advisor professor called me worried asking where I was. My professor was a great host, and he was neither your typical Japanese. He welcomed me in a Hawaiian shirt, a shark tooth necklace and an office carelessly full of memorabilia from other countries. I was fascinated. He gave me a tour through the university, Nara Women’s University is an undeniable historical mark in the Kansai area. His love for his job and for the institution calmed my initial anxiety for the town. Nara is the suburban prefecture between the very busy Osaka and Kyoto. Most of the families of the people that work in those cities live in Nara where they can raise their children in a peaceful environment. Nara’s main attraction is Nara Park, which is the closest to Kintetsu Nara Station. That’s the park with the deer where everybody takes pictures. There are not only deer though, there are temples and shrines in it, like Kofukuji, Todaiji and Kaisuga Taisha the Shinto shrine that reigns over the sacred park. In the park Buddhism and Shintoism co-exist without any trouble, like they do all throughout Japan. But the most important part of the park is that it holds the very history of Nara, the beliefs and hopes of the Japanese for centuries had been pour on the path ways of the park and in the halls of the shrine. A history that people from all over Japan feeds every end of December when they come to ask for blessings for the rest of the New Year. The park is not the only piece of history in the city, the old Nara city is also a place worth visiting. With laws preventing the construction of newer building structures, in every corner of Nara it is possible to find a hint of what the good old times looked like. The temples and places worth visit extend all over the prefecture far from the main city of Nara, like the Horyuji temple, one of the oldest and owner of the oldest wooden structure in the country. The temple is almost a secret to foreign visitors which makes it a better tip. Nara is a great walk for visitors, but it also has tour buses and train stations in and to the best places if the weather is not that great or if you don’t feel like walking and hiking. Needless to say, it’s a great place to live.

Nara helped me to re-encounter with peace, my peace, inner peace. It helped me re-encounter with my own journalistic curiosity which, ironically, had been lost somewhere within the monotonous layers of the everyday practice of journalism. However the main teaching was about time, about how it is not lost. Time or life, they don’t stop after the age of 29, traveling around the world is not only for twenty year olds, taking life changing decisions can be done at any age. So, if you think you are too old for coming to Japan, finding out that you are not will be the first lesson that this country will teach you.

Written by Erica Gonzalez