I have had more than three years of intensive experience with the Japanese tea ceremony. The more it goes, the more I see the tea room as a place to clear your thoughts. This is what I will write about here.

Reaching minimalism with tea

The Japanese interior design, at least the traditional one, has very often been described as « minimalist », fond of emptiness, insistent on restricting the number of items. But why is that ? Though it has many roots in an infinite number of details of the Japanese lifestyle and its history, there are certain elements of modern Japanese interiors that come directly from the Japanese tea room of the late 16th century. Though most of its characteristics existed before that time, they aggregated and became more popular at that moment.

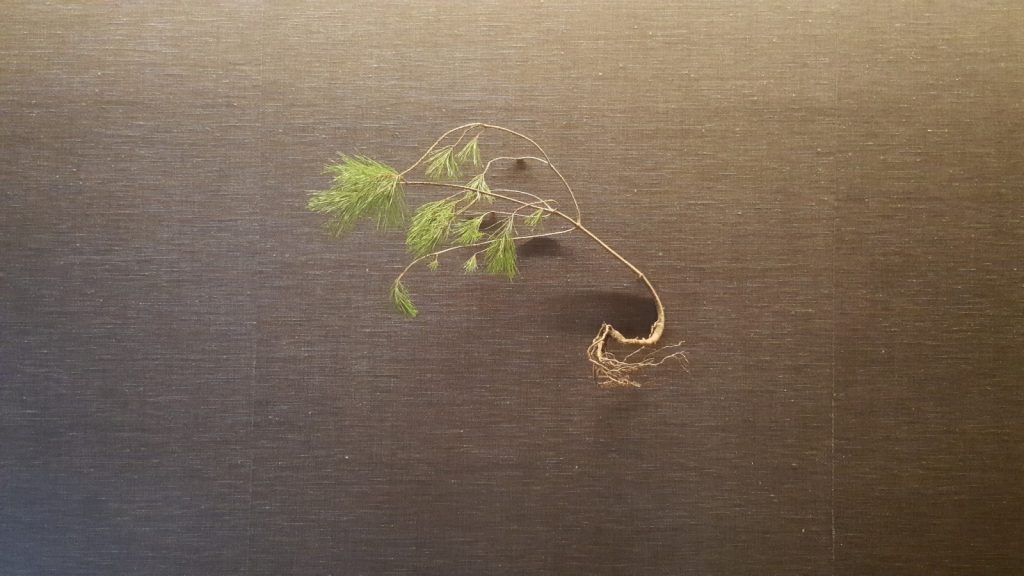

When entering a tea room, a guest must immediately notice were the tokonoma, the alcove, is. A Tokonoma used to be a place where the most important person sit. It is generally elevated or at least made of a different material compared to the other floors. Progressively, it has been turned into a place preserved for the gods and the display of the works of art that will define the theme of the ceremony. A calligraphy, a flower arrangement and a bit of incense wood. That is all. The calligraphy indicates a poem, a thought or even just a word that is enough to evoke the purpose of the gathering. The incense serves to purify the room. And the flowers…just a few of them, to evoke nature maybe. Few items if we compare this to a Thai Buddhist altar and its thousands of statues or a wealthy French church. But it is precisely because there are not many things that we notice them so well and that they stand out.

A single flower, a single hand

It is said that, one day, Hideyoshi Toyotomi, the ruler of Japan in the late 16th century, wanted to see the morning glory that his tea master Rikyu had planted in his tea garden. So he asked to be served tea. But when he arrived, the garden was void of any flower. Angry at this provocation, he entered the tea room and saw, in the middle of the alcove, a single morning glory. The feeling he got was beyond anything a field of morning glories could have made.

That story, I could experience it first hand in my own practice countless times. When preparing the flowers, we try to keep them to a minimum or to make sure that one of them stands out. In general, I never pick more than one flower now. It reminds me of an antique philosophy issue : when do grains of sands become a ‘bunch’ of grains. When does it become useless to count ? The eye can never discern a great number of things at the same time. We do not perceive this in our daily life, but our senses are constantly required by a swarm of elements that constantly pop up. And without even knowing it, we become concerned with our surroundings and we are not able to fully enjoy the present.

The same goes with our behavior. When I started making ceramics in Japan, I was doing a thousand flickering mouvements every minute and had poor results. My ceramic teacher, meanwhile, was slowly carving his tea bowls in no more than a dozen moves. Reaching simplicity, he was also reaching efficiency and could focus on something else : the actual shape he desired. His own actions, reduced to a minimum, were not bothering his thoughts.

And, finally, the same process happens in a tea room. Recently, as I was preparing tea, I felt that something was off. Though most people could not notice, I had this impression that my practice was a bit ‘shy’. Something inside of me was trying to escape from the situation of making tea. I wondered about it for weeks. And then I realized that my baby finger, when grabbing any item, was slightly loose. Many items do not need the support of this finger to be handled, but I was unconsciously letting it stray. My hand had become two : the fingers that acted and the one that wandered. On an insignificant scale, it was a mess, an occasion to divide my thoughts and lose control of them. So I rejoined my baby finger with the others.

The room for doubt

A tea master once told me : ‘in a tea room, what matters is not the rule. What matters is that there is a rule so there is no room for doubt and you can enter a state of meditation in action’. And indeed, as long as there is ‘no room for doubt’, the mind can calm itself and enter the realm of higher thoughts. Thinking back on the morning glory, a bunch of flowers and leaves going in every direction is so difficult to grasp visually. In a diluted way, any disorder evokes the dangers of a jungle, where a creature can spring at your throat from anywhere and at any moment. I am not saying that the same danger lied in Rikyu’s garden — though Hideyoshi might have thought about it — but I think that our brains are naturally designed to get progressively more worried as the disorder grows — at least a disorder that is not ‘ours’. The Japanese interior design is soothing for the mind because it gives little for the eyes to grip on. Hence, we feel more calm. There is no danger around. A paranoid samurai of old days can get really fond of this and so can we.

The arduous path to simplicity

Going back to the tea room, I realize how this emptiness is central to my practice. I always question myself : is this item or this flower truly necessary today ? And I remember all the flowers I cut down before realizing that only one was best. In the tea room, there is no distinction between the economy of means, the valorisation of things and the practice of a luxurious art. Because, deep down, the highest luxury is to have one profound experience, with clear thoughts and awe, of a single beautiful item, rather than the vague feeling got from seeing an entire collection, a ‘bunch’ of beauties. Great tea masters use tea bowls that sometimes are not seen for dozens of years. This may be a waste, but it makes their appearance so much more worthy and, when they do appear, they appear in a blank space, devoid of any distraction. Their true value, as beautiful items, is respected.

So, when I go to a tea ceremony, I sometimes think of this Chinese Mandarin that was told that a beautiful stone was on display. He said he would go in three hours. ‘Why so late ? asked the messenger ? — Because I need to dress myself properly for the stone’. Replied the Mandarin’. As I enter the tea room, I limit the wearing of patterns and bright colors, I avoid complex clothings and put everything I need in a single pouch. This way, just like the space I am about to enter, I hope to be simple enough that I do not worry my host and the other guests. Together, we can now clean our thoughts.

— All of this is just a very arduous path to simplicity.