It was on a sunny afternoon day of November 2016 that I met with my friend Yuko, at Kameoka station, east from Kyoto. At the time, I was doing my first internship in ceramics with James Erasmus that I talked about here. The reason why I came there on that day was to meet Sasaki Kyoshitsu, the fifth heir of the Shoraku Family. In other words : quite a big fish in the ceramic world.

Some months before, as I was trying to find an internship in Japan, Yuko had asked Sasaki if he would take me as an intern. The master said : ‘I may be able to receive him as an intern during Summer 2017… if he visits this winter.’ I did not know at the time how typically Japanese such an answer was. Japanese craftsmen believes in matter, concrete things, not in mails and vague demands. You have to visit them to convince them. But I had enough Japanese education in me to understand at that time that I had no choice anymore : my friend had introduced me, she would

loose face if I did not go. As crazy as it may seem, this meant that I had to go to Japan that winter, even just for one day, to potentially get an internship two seasons later.

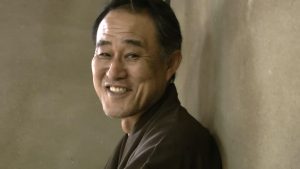

So here I was, on that cold and beautiful day of November, ready to meet Sasaki Kyoshitsu. I knew few things about him. I knew that he did not speak more English that I spoke Japanese. I knew that he was specialized in making Raku chawans, some of the most respected of all tea bowls. I also knew that, although the internship was not decided yet, he had already asked a friend living around if he could host me during my internship. And, finally, I knew that he liked to drink. So I had brought a bottle of Sauterne, a good French wine, very sweet. I did not know that Sasaki did not like sweet things. Later, he would be much happier with whisky.

So here I was, on that cold and beautiful day of November, ready to meet Sasaki Kyoshitsu. I knew few things about him. I knew that he did not speak more English that I spoke Japanese. I knew that he was specialized in making Raku chawans, some of the most respected of all tea bowls. I also knew that, although the internship was not decided yet, he had already asked a friend living around if he could host me during my internship. And, finally, I knew that he liked to drink. So I had brought a bottle of Sauterne, a good French wine, very sweet. I did not know that Sasaki did not like sweet things. Later, he would be much happier with whisky.

We sat down. I bowed many times. He talked with Yuko. I bowed again. He bowed to me.

He said : ‘ok’ with the embarrassed look of someone who is ashamed of his English.

Sasaki-sensei, as I call him now, is a very traditional man. He barely speaks, even in Japanese. He has his family and two employees to feed. He lives in his mountain, talking with the clay everyday of the week and even on days off. There is no need for Sensei to talk much. After all, his works speak for him.

IN November, I thanked him. Many times. I did not know exactly why, though there were many reasons. But I had no exact idea, and Sensei neither, of what I would do during three months at his workshop. Sensei simply said : ‘please, bring a camera, do a blog or something’.

Now, I also knew that this man was living surrounded by tea bowls in a beautiful house surrounded by mountains, with a wide open tea room where the light was pouring endlessly. In a way, it was enough to thank him for receiving me.

A ceramic internship with Mr. Erasmus and six months later, I was back. The adventure could start.

Theory and practice I certainly did not know the hardship that was waiting for me. Not that Sensei was harsh with me but I had miscalculated something : from my house (the ‘closest’) to the workshop, I had 6km to bicycle every morning…in the mountains. And I mean : up the mountain. With an old and rusty city bike and my shrimp-like strength. It took me about an hour and half every morning to go there, five times a week. I graduated from shrimp to lobster legs that summer.

Sweaty and tired, I was welcomed every morning by the earthy smell of the workshop and fresh water. Sensei was busy. He gave me a cushion and a place to work between him and his first son.

I was supposed to do everything like them. So I made my clay, I carved my tea bowls and I helped firing them. I filmed a lot, but badly. I wrote about it, and this was the start of my blog where, to this day, I continue to write.

Not speaking much Japanese, my conversations with Sensei and the other craftsmen were scarce. There were times, I felt really alone. Not knowing exactly what to do or what I was doing here, I often wondered if Sensei had the same questions in mind and I did not want to make him loose his time.

Not speaking much Japanese, my conversations with Sensei and the other craftsmen were scarce. There were times, I felt really alone. Not knowing exactly what to do or what I was doing here, I often wondered if Sensei had the same questions in mind and I did not want to make him loose his time.

Everyday, at lunch, we would both sit outside, looking at the mountain, breathing in the corrosive fragrance of summer and enjoying our simple meal. Sensei would start eating and, eventually say the same things to me : ‘Nessim, Kyo wa, ii tenki desu ne (It’s a beautiful day isn’t it ?)’ or ‘kyo wa, ame ga aru’ (it is raining today). I would answer hai (yes) and a short conversation would go on until one of us finished his meal.

Then Sensei would take a nap. That was about it. My Japanese did not make much progress at the time. But I learned to read between the lines and be grateful for any small attention. This is what the Japanese call ishin denshin : what the mind think, the heart conveys.

The making of a bowl Making tea bowls is not an easy job. To make a tea bowl in the ‘Raku’ way, one has to first take a big lump of clay and ‘mount’ it with his or her hand into a generic shape. Then, the lump dries a bit. After that, it is ‘carved’ into the definitive shape. That means extracting more than 75% of the original mass of clay ; until the walls and bottom of the tea bowl become very thin and the piece is quite light. At my Sensei’s kiln, the bowl is then fired once. Then the glaze is applied and a second firing happens. This is the theory.

The making of a bowl Making tea bowls is not an easy job. To make a tea bowl in the ‘Raku’ way, one has to first take a big lump of clay and ‘mount’ it with his or her hand into a generic shape. Then, the lump dries a bit. After that, it is ‘carved’ into the definitive shape. That means extracting more than 75% of the original mass of clay ; until the walls and bottom of the tea bowl become very thin and the piece is quite light. At my Sensei’s kiln, the bowl is then fired once. Then the glaze is applied and a second firing happens. This is the theory.

Many tourists and aficionados come to the workshop to make their own tea bowl in a single day.

They mount it, we dry the tea bowl fast and then they carve the shape. Sensei does the glaze and the two firings. He then ships the bowls to the home of the guest. Compared to these amateurs, I cannot say that I was very skilled. In three months, I made only a dozen of tea bowls and most of them were bad. Sensei buried them somewhere in his backyard and it is better that way.

In the meantime, I was helping around. I was serving the guests in the beautiful tea room, with the cicadas singing, pouring hot water in the masterpieces of my master’s ancestors. Sensei was nice enough to leave the tea room entirely to my care : I could invite anyone and so I did. I continued to write, film, take pictures, and tried to understand Sasaki-sensei through his art more than his words.

In the meantime, I was helping around. I was serving the guests in the beautiful tea room, with the cicadas singing, pouring hot water in the masterpieces of my master’s ancestors. Sensei was nice enough to leave the tea room entirely to my care : I could invite anyone and so I did. I continued to write, film, take pictures, and tried to understand Sasaki-sensei through his art more than his words.

Sasaki Kyoshitsu : a heart in a tea bowl Around the last month of my internship, I asked Sasaki-sensei to make an experiment. As I had seen him work so hard for others, I wanted to see a more personal side of him in his work. So I asked him to make two tea bowls that would not be sold : one for his sons, one for himself.

Sensei said that he had understood and started making them. I followed him during the whole process of their making, not knowing where this would lead.

When the first tea bowl came out of the gas kiln, my eyes got wider. The tea bowl Sensei had made was radically different from all his previous works. I had always admired the deepness of his black glaze. But this one was red, flamboyant and thick like lava. What did Sensei want to convey ? I looked at the burning tea bowl, amazed, and Sensei said that this tea bowl was for me.

I refused many times but he insisted. As a parting event, we made tea together. Sensei prepared the first tea in this lava tea bowl and I made tea for him in one my few successful creation.

Sensei asked me to convey the power of the Japanese crafts and tea ceremony and this is still what I do today. When I came back to Japan, he said that he considered me as his son and offered me a tea bowl made by his father, simply repeating ‘please, continue to study and work’.

Although we still do not communicate much, Sensei does everything he can to help me. I also help him around when I can, making tea during his exhibitions or promoting his work at various places. It seems normal to me now : we are family now.

If you wish to make your own tea bowl at Sasaki’s workshop, you can contact him through me or on his website. I will be delighted to act as a translator for you if needed