In Japan, cute stuff is not just for kids. It’s a cultural phenomenon for everyone!

One of the most common words you will hear in casual conversation in Japan is “kawaii!” Kawaii can be translated “cute” in English, but according to its etymology (word roots) it means “lovable.” By understanding kawaii, and what Japanese consider to be lovable, you will understand your Japanese friends, co-workers, and/or relatives better. Key characteristics include smallness, youth, naïveté, simplicity, pitifulness and, interestingly, anthropomorphism. These traits are present throughout Japanese history to the present, so let’s take a look.

The love of small things is quite practical. Way before the shinkansen, when traveling from city to city depended on one’s own two legs, people naturally chose compact, lightweight things over large, bulky things. Think bonsai (Kamakura Period, 1192-1333), the Walkman (1979), or the ultra small Japanese K-car.

In addition to practicality, smallness is also about aesthetics and emotion. In the famous work, “The Pillow Book,” Sei Shonnagon described various things considered “utsukushi,” (うつくし) in the Heian Period (794-1185): nail art depicting a child’s face, a human squeaking and pretending to be a mouse, and a crawling infant discovering a speck of dust and showing to its parent.

Cultural researcher and professional translator Matt Ault talks about the many cute cartoon characters that guide people through their everyday lives. If you live in Japan, you will know what he’s talking about. From the posters in train stations to official Tokyo Disaster Prevention Handbook, to leaflets explaining the dangers of scam phone calls, cute cartoons deliver sensitive information or address potentially stressful topics to the public. Their child-like innocence breaks tension and help draw out nurturing emotions from the viewer.

The same type of simplistic, charming kawaii is nothing new. The Tokyo National Museum houses an earthenware doorknob with a simple and innocent human face dating all the way back to the Jōmon period (~14000-1000 BC), long before Scrooge’s startling encounter with the spirit of Marley.

Jumping ahead to the Edo Period, farmers were looking for a way to make a little extra income, and they found their solution in selling kokeshi–wooden dolls with simple cylindrical bodies, spherical heads and hand-painted facial features. They were sold as souvenirs for visitors to hot springs 湯治客. Today, too, souvenir shops carry a mind-boggling array of merchandise, from baby bibs to masks to nail clippers, featuring their local mascot character. Apparently, sales of products can increase 20-30% thanks to these kawaii friends.

In Japan, everything has a face. Whether it be a rice ball in a bento box or a kiwifruit at the grocery store, kawaii turns on anthropomorphism. Even from the Edo Period (1603-1867), wood-block prints 浮世絵 of famous artists depict carp fish doing courtly activities, octopi wearing clothes and dancing on the seashore, and cats in kimono being waited on at inns.

Trivia Break: Who was the first artist to deliberately produce works in a kawaii style?

Hint: He is famous for his paintings of beautiful ladies and is associated with Taisho Romanticism 大正ロマン.

(Answer at the end of this post)

Today, we see anthropomorphism in the 800+ “yuru-kyara,” ゆるキャラ, the laid-back and friendly regional mascots that help out with local tourism and community projects. Yuru-kyara are usually an animal, a regional specialty, or a character from local folklore. Probably the most famous is Kumamon, a black bear with red cheeks from Kumamoto Prefecture. In order to register as a yuru-kyara, a mascot must serve the public in one of three ways: by contributing to the region, by contributing to the small businesses, or by contributing to Japan as a whole. This could be through tourism or revitalization efforts. Every year, these mascots gather for a Yuru Kyara Grand Prix, where the public can meet, greet, and vote on their favorite mascots. Of course, you can line up to buy merch, too! With the corona-virus cancellations, it’s hard to say whether or not there will be a Grand Prix in 2021, but there is no doubt the mascots will be putting in double the effort to support their communities and keep people’s spirits up.

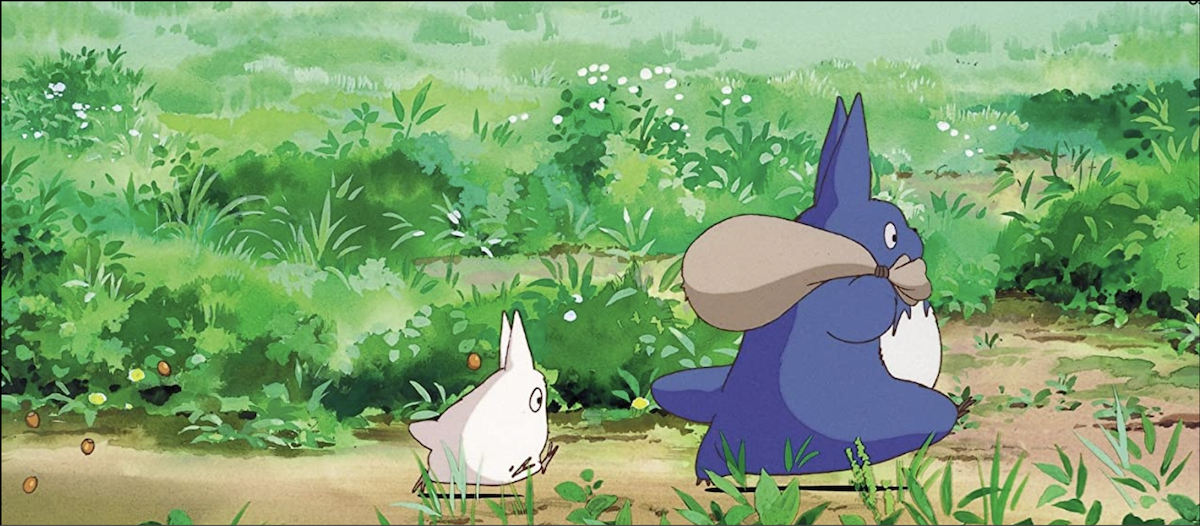

All these concepts: smallness, youth, naïveté, simplicity, pitifulness and anthropomorphism are best understood through an example, so let’s take a look at Studio Ghibli’s My Neighbor Totoro. If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s a must! Titular character, Totoro, is big enough to serve as a living trampoline, but he has two companions who truly reflect kawaii ideals. One is a blue replica of full-size Totoro, but mini size. The other is a mini-mini white, version of the two, with similar pointy ears but with no mouth or nose–only a pair of wide round eyes. These two small Totoros are easily scared off, and although they don’t speak, blue Totoro carries a traveler’s sack over his shoulder like a human wayfarer, and all three Totoro participate in a midnight ocarina ensemble.

There is much more to be said on kawaii as it pertains to the perception of beauty, gaming, and pop culture, but I’ll leave that for another post. In the meantime, what else do you think defines the Japanese concept of kawaii? How is it the same or different from the idea of cuteness in your country?

Trivia Answer: Takehisa Yumeji